CEU (Continuing Education Unit): 2 Credits

Educational aims and objectives

This clinical article aims to consider and assess risk factors associated with increased risk of endodontic-related nerve injury.

Expected outcomes

Endodontic Practice US subscribers can answer the CE questions to earn 2 hours of CE from reading this article. Correctly answering the questions will demonstrate the reader can:

- Consider and assess risk factors associated with increased risk of nerve injury.

- Understand the diagnostic features of endodontic-related nerve injuries with particular

emphasis on the possible 2- to 3-day delay in presentation after treatment. - Recognize the urgency with which these nerve injuries must be recognized, assessed, and managed if the resolution of nerve injury is too maximized.

In the final part of two articles, Dr. Tara Renton explores risk assessment, diagnosis, and management of endodontic-related nerve injuries

In part 1 of this clinical article, the author examined the risk factors and consequences of endodontic-related nerve injuries. Here, the author looks at the risk assessment, diagnosis, and management of endodontic-related nerve injuries, as well as recommendations using the literature.

Minimizing risk

Risk assessment of the patient and dental factors are very important. Patients over the age of 50 are less likely to recover from nerve injury. Certain medical conditions may predispose your patient to developing chronic post-traumatic neuropathy and/or pain (existing fibromyalgia, migraines, Raynaud’s disease, IBS, and psychological morbidity). Pre-screening of dental neuropathic pain is advised before undertaking repeated endodontics or further interventional surgery.

A key factor in these cases appears to be proximity of the tooth apex to the inferior dental canal (IDC). The mandibular premolars located close to the mental foramina are considered high risk in orthodontics for potential nerve damage (Knowles, Jergenson, Howard, 2003; Baxmann, 2006; Scarano, et al., 2007).

A key factor in these cases appears to be proximity of the tooth apex to the inferior dental canal (IDC). The mandibular premolars located close to the mental foramina are considered high risk in orthodontics for potential nerve damage (Knowles, Jergenson, Howard, 2003; Baxmann, 2006; Scarano, et al., 2007).

An important factor often overlooked in endodontics is the “safety zone,” often referred to during estimation of drilling depths for implant preparation surgery. A single paper addresses the notion that endodontists should consider the distance between the tooth apex and the inferior dental canal (IDC estimated on a plain film not necessarily by a cone beam computed tomography [CBCT]) to ensure that accidental apical leakage or over-instrumentation will more likely cause nerve injury if the apex is adjacent to the IDC (Ngeow, 2010).

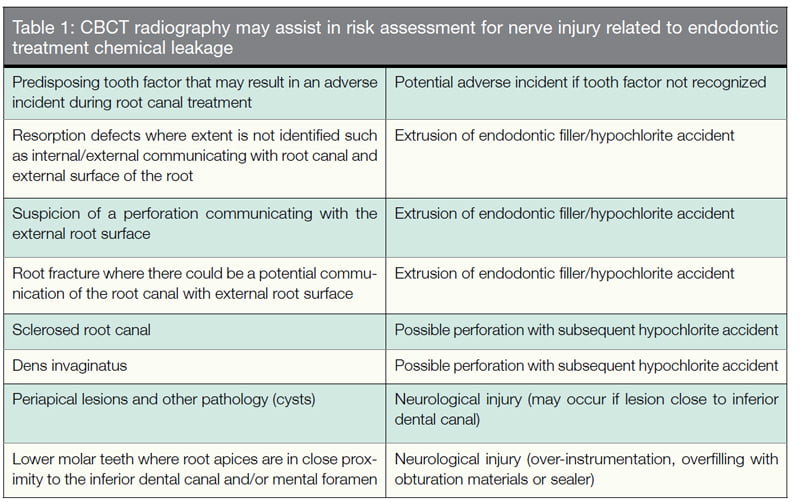

Assessment of other dental factors, including root fractures and periapical lesions (Table 1) must also be assessed. Assessing the actual position of the IDC, mental loop, and accessory canals can be complex, and the clinician involved in treatment planning must be able to analyze and risk-assess radiological investigations and not leave the risk assessment to another clinician. There continues to be considerable debate as to whether CBCT is superior in assessing these risk factors.

Minimizing technical causes

Apical extrusion of products may be increased by ultrasonics and minimized by using EndoVac. Postoperative root canal treatment views must be arranged on the day of completion of the treatment, and identification of any root canal treatment product in the inferior alveolar nerve (IAN) canal should be reviewed carefully and removed within 48 hours (Helvacıog˘lu Kivanç, 2015). A systematic review made a specific recommendation in care when preventing extrusion of endo materials into the IDC (Olsen, et al., 2014).

CBCT guidance

CBCT guidance

All radiographic examinations must be justified on an individual needs basis whereby the benefits to the patient of each exposure must outweigh the risks. In no case may the exposure of patients to X-rays be considered “routine,” and certainly CBCT examinations should not be done without initially obtaining a thorough medical history and clinical examination. CBCT should only be considered an adjunct to two-dimensional imaging in dentistry (American Association of Endodontists, American Academy of Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology, 2011).

Risk assessment — location of the inferior dental canal

- A classic study of the relationship between mandibular premolar apices and the mental foramen has reported close proximity with the first premolar apex in 15.4% of patients and with the second premolar apex in 13.9% of patients (Fishel, et al., 1976).

- In their morphometric study, Phillips and colleagues reported that each mental foramen was located an average distance of 2.18 mm mesially and 2.4 mm inferiorly from the radiographic apex of the second premolar (Phillips, Weller, Kulild, 1992).

- More precisely, each mental foramen was found to be located, on average, anywhere between 3.8 mm mesial, 2.7 mm distal, 3.4 mm above, or 3.5 mm below the apex of the respective second premolar (Phillips, Weller, Kulild, 1992).

- In contrast, the apex of each second premolar was between 0 mm and 4.7 mm from the respective mental foramen in various cadaveric studies (Denio, Torabinejad, Bakland, 1992).

Is CBCT better than long cone periapical radiographs (LCPA) for risk assessment?

Periapical pathology diagnosis using CBCT revealed a significantly lower number of favorable outcomes than periapicals in root canal retreatment. This significantly affected the future management of cases attending for a review (Davies, et al., 2015).

In a study by Chavda and colleagues (2014), 21 unsalvageable teeth from 20 patients that had been radiographed and scanned with CBCT imaging were included to look at root fractures. The teeth were atraumatically extracted and visually inspected under a microscope to confirm the presence/absence of fracture. Both digital radiography and CBCT imaging have significant limitations when detecting vertical root fractures.

Is dose reduction possible in CBCT?

Limited field-of-view CBCT systems can provide images of several teeth from approximately the same radiation dose as two periapical radiographs, and they may provide a dose savings over multiple traditional images in complex cases.

Both 360° and 180° CBCT scans yielded similar accuracy in the detection of artificial bone lesions. The use of 180° scans might be advisable to reduce the radiation dose to the patient in line with the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) guidance to use as low a dosage as reasonably achievable (Lennon, et al., 2011).

Diagnosis and assessment

A previous literature review of paresthesia in endodontics recommended that the clinician must carry out a complete medical history, panoramic and periapical radiography, and (in some cases) computed tomography, as well as mechanoreceptive and nociceptive tests.

It is important to recognize that inferior alveolar nerve injuries (IANI) can occur due to local anesthetic block injections, and the clinician can often discriminate between endodontic and local anesthesia-caused nerve injuries by careful questioning and clinical neurological assessment.

Chemical nerve injury may not be obvious radiographically:

- If the patient is suffering from neuropathy after the local anesthetic has worn off and the postoperative radiographs confirm that there is no radiopaque material in the canal, chemical nerve injury may be presumed.

- Mapping of the neuropathic area will discriminate between inferior dental block (IDB) and endodontic nerve injury.

- This may be an irreversible injury to the nerve and subsequent, even swift, removal of the root canal filling or tooth is unlikely to resolve the nerve injury.

- If there is material recognized within the canal, this would suggest injury, but if there is no material in the canal, is the same presumption made?

The patients must be assessed holistically, including their history of the event, and if it is related to the initiation of pain. Ensure that the pain history excludes pre-existing neuropathic pain, including:

- Severe pain during procedure (funny-bone pain)

- High level post-surgical pain (indicative of nerve injury)

- Ongoing pain, altered sensation and/or numbness

- Functional problems

- Psychological issues

Important questions about the mechanism and duration of the neuropathy will drive the timing and type of management (Renton, et al., 2006). Necessary investigations include:

- Radiological: LCPA; CBCT necessary post-trauma.

- Neurosensory to confirm that the presence of a neuropathy and distribution correlates with potential nerve injury.

- Diagnostic local anesthesia blocks may be useful in evaluating the potential of some peripheral pain management strategies when medical management is unsuccessful.

Management is that of the patient with the nerve injury not the neuropathy itself (Renton, Yilmaz, 2012). Grötz and colleagues (1998) reported on 11 patients with endodontic-associated neuropathy and their management. They similarly reported that the neurological findings were dominated by hypesthesia and dysesthesia, with 50% of patients reporting pain. Initial X-rays showed root filling material in the area of the mandibular canal. Nine cases were treated with apicectomy and decompression of the nerve: In two cases, extraction of the tooth was necessary; only one patient reported persistent pain after surgery. Primarily, all patients should have an apology and explanation (duty of candor) by the treating clinician.

Management tools may include counseling for all patients with nerve injuries, which is very effective (there is limited evidence for success of this treatment for endodontic-related IANIs, but evidence does support psychological therapies for chronic pain and IANIs) (Renton, Yilmaz, 2011) for:

- Local anesthesia, orthognathic fracture

- Endodontic or implant injuries greater than 30 hours

- TMS injuries older than 6 months

Counseling includes reaffirming nerve injury is permanent and reassurance and explanation. Other management tools include medical symptomatic therapy (pain or discomfort) through topical and systemic agents for pain.

Lastly, surgical exploration is significant:

- Remove implant or endodontic material within 24 hours.

- Explore IAN injuries through socket in less than 4 weeks.

- Explore LN injuries before 12 weeks.

Surgical management

- Repeat endodontic treatment with removal of the overfill or over-instrumentation. There are many reports of repeated endodontic treatment for IANIs related to endodontics; however, the outcomes remain poor (Nayak, et al., 2011; Yatsuhashi, et al., 2003).

- Surgical excision of the overfill of chemicals and endodontic root fillers: Pogrel (2007) reported 11 cases of acute surgical intervention with five patients reporting improvement, and two none. On this basis, Pogrel recommends urgent (under 24 hours) surgical exploration with aggressive irrigation and removal of overfill. Several report cases successfully treated using urgent surgical treatment (Scala, et al., 2014; Scolozzi, Lombardi, Jacques, 2004; Brkic´, Gürkan-Köseog˘lu, Olgac, 2009). A similar protocol is recommended for sodium hydroxide neuropathies (Byun, et al., 2015).

- Medical management to minimize acute surgical neural inflammation by using NSAIDs and prednisolone-mimic protocols undertaken for other acute sensory nerve injuries (Gatot, Tovi, 1986; Grötz, et al., 1998).

- Medical management of chronic pain associated with endodontic treatment: Oshima (2009) reported that 16 out of 271 patients presenting with chronic orofacial pain were diagnosed with chronic neuropathic tooth pain subsequent to endodontic retreatment. Most of these patients were treated for maxillary teeth. Seventy percent of the patients responded to tricyclic antidepressant therapy, which highlights the importance of establishing whether the patient has neuropathic pain.

In Renton and Yilmaz’s (2012) study, all the patients presented too late for surgical decompression, or it was not indicated. Thus, two patients were managed with oxcarbazepine for neuralgic pain elicited with touch or cold and with topical clonazepam intraorally to manage the severe gingival discomfort.

Two patients were prescribed topical 5% lidocaine patches (12 hours on nocte and 12 hours off daily) for debilitating mechanical allodynia in the extraoral dermatome of the IAN, causing pain and functional problems. This is a treatment used successfully for patients with chronic orofacial pain, particularly those with mechanical or cold allodynia of the face.

Recommendations for treatment of trigeminal neuropathic pain are also well described by Renton and Zakzrewska (2010) (Alonso-Ezpeleta, et al., 2014).

Timing of treatment

Nerve tissue is incredibly sensitive to pH changes; thus, chemical nerve injuries are commonly permanent and often cause severe neuropathic pain. These chemical nerve injuries often cause severe neuropathic pain.

If the patient is suffering from neuropathy after the local anesthesia has worn off, and the postoperative radiographs (not CBCT) confirm that there is no radiopaque material in the canal, chemical nerve injury may be presumed. This may be an irreversible injury to the nerve, and subsequent “swift” removal of the root canal treatment or tooth extraction is unlikely to result in resolution of the nerve injury (Pogrel, 2007).

Management and timing

Acute management (greater than 30 hours)

Confirm overfill/neuropathy. In some reports, 20% of the nerve injuries are delayed in presentation, and the endodontist may need to warn the patient that onset of altered sensation, pain, and/or numbness up to 3 to 4 days post-endodontic treatment must immediately be reported.

Treatment should be considered within 30 hours of neuropathy presentation to minimize permanency of nerve injury while maximizing resolution.

- Consider endodontic retreatment (Yatsuhashi, et al., 2003)

- If there is extensive overfill in IDC, refer urgently for extraction, apicoectomy or IAN decompression.

Later management

If minimal or no symptoms are present, reassure and review (duty of candor).

For mild symptoms, such as small neuropathic area, low discomfort:

- Reassurance/topical Versatis patches (5% lidocaine patches).

- Some authors recommend steroid therapy for early postoperative neuritis (Gatot, Tovi, 1986).

For moderate symptoms, such as a larger neuropathic area, functional and psychological implications, discomfort/pain:

- Systemic medical management (nortriptyline, pregabalin)

- Referral for psychological support

- Review

For severe symptoms:

- Systemic medical management (nortriptyline, pregabalin)

- Referral for psychological support

- Review

- Pain management referral (possible interventional procedures) (Kim, et al., 2013); and Botox (Ngeow, 2010)

Recommendations

Based on current evidence, dental practitioners undertaking endodontic treatment should:

- Not attempt root canal treatment (RCT) in teeth close to the IDC; instead, they should refer for specialist care.

- Screen out neuropathic pain pre-RCT.

- Risk-assess, including identifying dental risk factors (+/- CBCT case dependent), such as teeth in close proximity to the inferior alveolar nerve, and take special care to prevent over-instrumentation and the extrusion of irrigants and materials into the periapical tissues; root fractures; resorption; apical pathology.

- To prevent overfill or extrusion, consider: creating an apical stop or dentin apical plug; make sure the preparation has taper and hence resistance form; obturating shorter; using cold lateral condensation to gain apical control; do not use resin-based sealers such as AH Plus® sealer.

- Avoid over-instrumentation: care with instrumentation and patency filing may have to work shorter; care using intracanal medicament (for example, calcium hydroxide) — do not syringe down to full working length; deliver more coronally; use a file to deliver the calcium hydroxide toward the apical part of the canal.

- Record any events that may indicate operative nerve injury, including extreme pain during LA IDB, canal instrumentation, irrigation, medication, or filling; and sudden and profuse hemorrhage arising from the apex of the tooth.

- Take appropriate postoperative periapical radiographs to check for any extrusion of dressing or filling materials into the inferior dental canal or around the mental foramen.

- Home check, and if signs of persistent or new neuropathy: remove overfill urgently (30 hours); no antibiotics; recommend vitamin B, NSAIDs, steroids, prednisolone (step down 15 mg for 5 days, 10 mg for 5 days, and 5 mg 5 days), and high dose NSAIDs, 600 mg ibuprofen and make a timely referral to an appropriately trained neurosurgeon, if necessary; long-term therapeutic management.

Conclusion

In this article, the author aims to have highlighted many areas of poor evidence base for prevention, assessment, and management of IANIs related to endodontic treatment; but in addition, focus attention on some areas where improved risk assessment and avoidance of these nerve injuries is possible.

References

- AAE and AAOMR joint position statement. Use of cone-beam-computed tomography in endodontics. Pa Dent J (Harrisb). 2011;78(1):37-39.

- Alonso-Ezpeleta O, Martín PJ, López-López J, Castellanos-Cosano L, Martín-González J, Segura-Egea JJ. Pregabalin in the treatment of inferior alveolar nerve paraesthesia following overfilling of endodontic sealer. J Clin Exp Dent. 2014;6(2):e197-e202.

- American Association of Endodontists; American Academy of Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology. Use of cone-beam computed tomography in endodontics Joint Position Statement of the American Association of Endodontists and the American Academy of Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;111(2):234-237.

- Baxmann M. Mental paresthesia and orthodontic treatment. Angle Orthod. 2006;76(3):533-537.

- Brkić A, Gürkan-Köseoğlu B, Olgac V. Surgical approach to iatrogenic complications of endodontic therapy: a report of 2 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;107(5): e50-e53.

- Byun SH, Kim SS, Chung HJ, et al. Surgical management of damaged inferior alveolar nerve caused by endodontic overfilling of calcium hydroxide paste. Int Endod J. 2016;49(11):1020-1029.

- Chavda R, Mannocci F, Andiappan M, Patel S. Comparing the in vivo diagnostic accuracy of digital periapical radiography with cone beam computed tomography for the detection of vertical root fracture. J Endod. 2014; 40(10):1524-1529.

- Denio D, Torabinejad M, Bakland LK. Anatomical relationship of the mandibular canal to its surrounding structures in mature mandibles. J Endod. 1992;18(4):161-165.

- Fishel D, Buchner A, Hershkowith A, Kaffe I. Roentgenologic study of the mental foramen. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1976; 41(5):682-686.

- Gatot A, Tovi F. Prednisone treatment for injury and compression of inferior alveolar nerve: report of a case of anesthesia following endodontic overfilling. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1986;62(6):704-709.

- Grötz KA, Al-Nawas B, de Aguiar EG, Schulz A, Wagner W. Treatment of injuries to the inferior alveolar nerve after endodontic procedures. Clin Oral Investig. 1998;2(2):73-76.

- Helvacıoğlu Kıvanç B, Deniz Arısu H, Yanar NÖ, Silah HM, İnam R, Görgül G. Apical extrusion of sodium hypochlorite activated with two laser systems and ultrasonics: a spectrophotometric analysis. BMC Oral Health. 2015;15(1):71.

- Kim JH, Yu HY, Park SY, Lee SC, Kim YC. Pulsed and conventional radiofrequency treatment: which is effective for dental procedure-related symptomatic trigeminal neuralgia? Pain Med. 2013;14(3):430-435.

- Knowles KI, Jergenson MA, Howard JH. Paresthesia associated with endodontic treatment of mandibular premolars. J Endod. 2003;29(11):768-770.

- Lennon S, Patel S, Foschi F, Wilson R, Davies J, Mannocci F. Diagnostic accuracy of limited-volume cone-beam computed tomography in the detection of periapical bone loss: 360° scans versus 180° scans. Int Endod J. 2011;44(12):1118-1127.

- Nayak RN, Hiremath S, Shaikh S, Nayak AR. Dysesthesia with pain due to a broken endodontic instrument lodged in the mandibular canal — a simple deroofing technique for its retrieval: case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;111(2):e48-e51.

- Ngeow WC . Is there a “safety zone” in the mandibular premolar region where damage to the mental nerve can be avoided if periapical extrusion occurs? J Can Dent Assoc. 2010;76:a61.

- Ngeow WC, Nair R. Injection of botulinum toxin type A (BOTOX) into trigger zone of trigeminal neuralgia as a means to control pain. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;109(3):e47-e50.

- Olsen JJ, Thorn JJ, Korsgaard N, Pinholt EM. Nerve lesions following apical extrusion of non-setting calcium hydroxide: a systematic case review and report of two cases. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2014;42(6):757-762.

- Oshima K, Ishii T, Ogura Y, Aoyama Y, Katsuumi I. Clinical investigation of patients who develop neuropathic tooth pain after endodontics procedures. J Endod. 2009;35(7):958-961.

- Patel S, Wilson R, Dawood F, Foschi F, Mannocci F. The detection of periapical pathosis using digital periapical radiography and cone beam computed tomography in endodontically retreated teeth — part 2: a 1-year post-treatment follow-up. Int Endod J. 2012;45(8):711-723.

- Phillips JL, Weller RN, Kulild JC. The mental foramen: 2. Radiographic position in relation to the mandibular second premolar. J Endod. 1992;18(6):271-274.

- Pogrel MA. Damage to the inferior alveolar nerve as the result of root canal therapy. J Am Dent Assoc. 2007;138(1):65-69.

- Renton T, Thexton A, Crean SJ, Hankins M. Simplifying the assessment of the recovery from surgical injury to the lingual nerve. Br Dent J. 2006;200(10):569-573.

- Renton T, Yilmaz Z. Profiling of patients presenting with posttraumatic neuropathy of the trigeminal nerve. J Orofac Pain. 2011;25(4):333-344.

- Renton T, Yilmaz Z. Managing iatrogenic trigeminal nerve injury: a case series and review of the literature. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;41(5):629-637.

- Renton T, Zakrzewska JM: Orofacial pain. In: Shaw I, Kumar C, Dodds C, eds. Oxford Textbook of Anaesthesia for Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. Oxford:Oxford University Press; 2010.

- Scala R, Cucchi A, Cappellina L, Ghensi P. Cleaning and decompression of inferior alveolar canal to treat dysesthesia and paresthesia following endodontic treatment of a third molar. Indian J Dent Res. 2014;25(3):413-415.

- Scarano A, Di Carlo F, Quaranta A, Piattelli A. Injury of the inferior alveolar nerve after overfilling of the root canal with endodontic cement: a case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;104(1):e56-e59.

- Scolozzi P, Lombardi T, Jaques B. Successful inferior alveolar nerve decompression for dysesthesia following endodontic treatment: report of 4 cases treated by mandibular sagittal osteotomy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2004;97(5):625-631.

- Yatsuhashi T, Nakagawa K, Matsumoto M, et al. Inferior alveolar nerve paresthesia relieved by microscopic endodontic treatment. Bull Tokyo Dent Coll. 2003; 44(4):209-212.

Stay Relevant With Endodontic Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and more..