CEU (Continuing Education Unit): 2 Credits

Educational aims and objectives

This clinical article aims to explain the benefits and limitations of CBCT and digital imaging

in endodontics.

Expected outcomes

Endodontic Practice US subscribers can answer the CE questions to earn 2 hours of CE from reading this article. Correctly answering the questions will demonstrate the reader can:

- Identify some differences in the diagnostic abilities of 2D- and 3D-imaging technologies.

- Identify the technology behind CBCT imaging.

- Realize the management of CBCT in endodontics.

- Recognize the benefits and limitations of CBCT.

- Recognize the importance of assessing patients on an individual basis.

Dr. Alix Davies discusses the use of CBCT in endodontics

Cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) is one of the most significant advances in endodontics in the last decade. When used appropriately, it can greatly enhance the diagnosis and treatment planning of a variety of endodontic cases. However, it is important that each case is considered individually to ensure that the benefits provided by the scan outweigh the risks of the additional radiation.

Cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) is one of the most significant advances in endodontics in the last decade. When used appropriately, it can greatly enhance the diagnosis and treatment planning of a variety of endodontic cases. However, it is important that each case is considered individually to ensure that the benefits provided by the scan outweigh the risks of the additional radiation.

Recent European Society of Endodontology (ESE) guidelines (Patel, et al., 2014) on the use of CBCT in endodontics suggest scenarios where a scan may be useful (Table 1). This article aims to explore these scenarios, discussing situations where CBCT would be useful, and those where it would provide no additional benefit to management of the case.

CBCT technology

Radiographic examination is essential in the diagnosis and management of endodontic problems and is performed with a periapical radiograph. However, a single periapical has limited diagnostic ability due to anatomical noise from superimposed structures, such as the maxillary sinus, zygomatic arch, and inferior dental nerve (Huumonen, Ørstavik, 2002; Patel, et al., 2009). The three-dimensional anatomy is compressed into a two-dimensional image, which will result in superimposition of the roots and prevent full appreciation of the root canal anatomy. Apical periodontitis is also difficult to diagnose in periapical radiographs when the lesions are confined to cancellous bone, especially when covered by a thick cortical plate (Bender, Seltzer 1961; Huumonen, Ørstavik, 2002).

A CBCT is an extraoral imaging technique involving a cone-shaped beam and radiographic detector, which orbit around the patient. The data that is collected is reconstructed to produce three-dimensional scans of the maxillofacial region. These can be viewed in multiple planes to assess the presence of periapical lesions, root canal morphology, and the surrounding dentoalveolar anatomy. This increased knowledge may influence management decisions and treatment approaches (Davies, et al., 2015; Davies, et al., 2016; Patel, et al., 2009).

The effective dose of a periapical radiograph is 1-5µSv (Gijbels, et al., 2002) while the dose of CBCT with the Accuitomo (J. Morita USA) (4×4 cm field of view) ranges from 13µSv to 44µSv (Loubele, et al., 2009). The radiation dose received by the patient varies depending on the field of view (FOV), exposure time, tube current and potential, and the region of the jaw that is undergoing the scan.

Clinicans who order CBCT scans must have appropriate training (Brown, et al., 2014) and must ensure that radiation doses to patients are as low as reasonably achievable (ALARA). The need for a CBCT must be justified, due not only to the additional radiation that the patient will be exposed to, but also to the extra cost, and possibly travel time required for the patient to undergo the scan. Increasing numbers of dental practices have in-house CBCT scanners. However, many of these were designed for implant and oral surgery assessment, producing larger volume, lower resolution scans that are unsuitable for endodontic cases. Recent models have an endodontic function that enables a small volume higher resolution (75-125µm) scan to be taken. This is necessary to maximize the information gained while minimizing the dose to the patient.

The applications of CBCT in endodontics

Diagnosis of periapical pathology

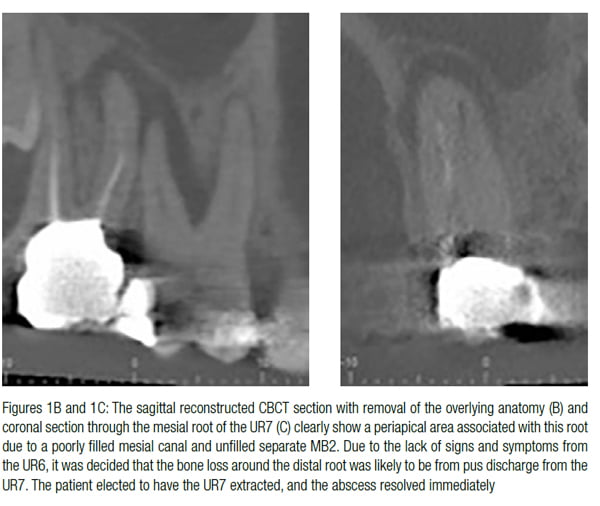

CBCTs are more specific and sensitive in the diagnosis of periapical pathology than periapical radiographs (Stavropoulos, Wenzel, 2007; Özen, et al., 2009; Patel, et al., 2009). They may, therefore, assist in locating an offending tooth when signs and symptoms are inconsistent (Figures 1A-1C). They may also be used to confirm the absence of an odontogenic etiology and therefore assist in the diagnosis of non-odontogenic causes of pain (Patel, et al., 2015).

Diagnosis of vertical root fracture

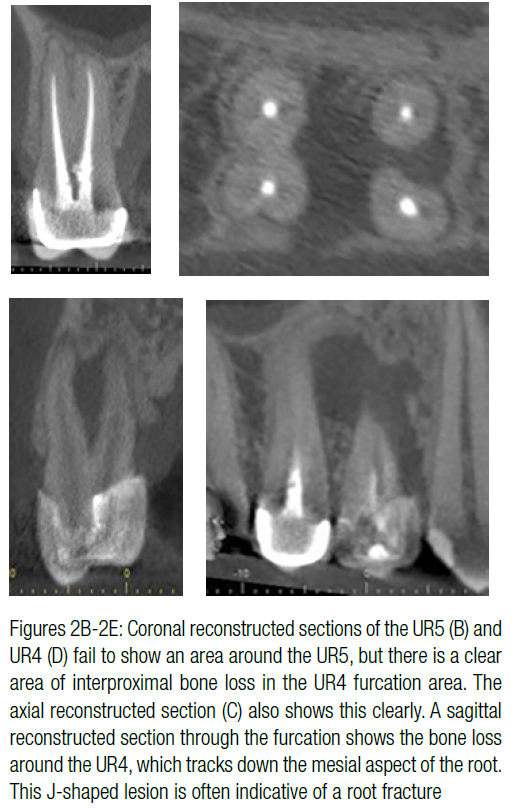

CBCT scans cannot reliably detect small cracks or incomplete vertical root fractures (Chang, et al., 2016). Larger fractures are likely to be evident clinically or on periapical radiographs, and a CBCT would therefore not be indicated. CBCT is particularly unreliable in detecting vertical root fractures in root-filled teeth, as the image scatter produced by the root filling will mask the area of the root that needs to be assessed (Patel, et al., 2013). However, the J-shaped radiolucencies that often indicate a root fracture may be more clearly visible once superimposed structures, such as roots, are removed, thus assisting the clinician in reaching a diagnosis (Figures 2A-2E).

Dentoalveolar trauma

Dentoalveolar trauma

CBCT may be used to assess dentoalveolar trauma in cases where clinical and conventional radiographic assessments are inconclusive (Patel, et al., 2015). Multiple periapicals are currently recommended to assess for fractures (Diangelis, et al., 2012), but these may still fail to show a horizontal fracture if the radiographic beam does not pass directly through the fracture line (Orhan, Aksoy, Kalender, 2010). The exact location of oblique fractures may, in particular, be more clearly diagnosed with CBCT and therefore more appropriately managed (Bornstein, et al., 2009). Patients are likely to find the extraoral CBCT imaging technique far more comfortable than tolerating intraoral beam holders, especially when teeth are mobile or fractured, or there are soft tissue lacerations. Nonetheless, it is important that the request for a CBCT does not delay emergency treatment if the facilities are not immediately available.

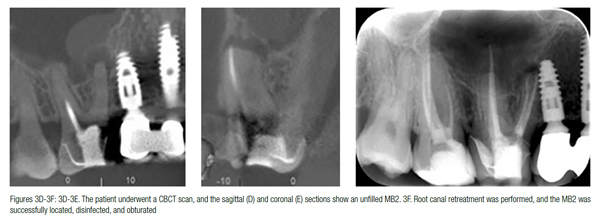

Assessment of complex root canal anatomy

Each tooth demonstrates a variety of canal configurations that must be thoroughly disinfected to maximize success rates of root canal treatment. An experienced clinician working with a microscope would be expected to identify the canals in the majority of cases, and therefore routine use of CBCT for every case is not justified. However, cases with unusual root formations, such as dens in dente (tooth within a tooth) (Durack, Patel, 2011), multi-rooted lower premolars, C-shaped molars, or cases with excessively curved canals, may benefit from a CBCT scan. A case where the root treatment was performed to a good standard and has still failed may also require additional imaging to assess for unfilled canals (Figures 3A-3F).

CBCT has been shown to identify significantly more canals in root-filled teeth than periapicals alone (Davies, et al., 2015). However, scans should not be taken to compensate for lackadaisical diagnostic or clinical skills. It is also important that the clinician has the equipment and skill set to make appropriate use of the additional information gained from the scan. There is little point in taking a CBCT to assess for an unfilled MB2 canal if a lack of magnification and skills would still preclude its discovery.

CBCT has been shown to identify significantly more canals in root-filled teeth than periapicals alone (Davies, et al., 2015). However, scans should not be taken to compensate for lackadaisical diagnostic or clinical skills. It is also important that the clinician has the equipment and skill set to make appropriate use of the additional information gained from the scan. There is little point in taking a CBCT to assess for an unfilled MB2 canal if a lack of magnification and skills would still preclude its discovery.

Canal sclerosis is a common challenge to adequately disinfecting the canals. CBCT may, however, be of minimal benefit in assisting with the location of the canal as the resolution is significantly worse than that of a periapical radiograph. Therefore, if the radiograph did not reveal a canal, it would be unlikely be visible with CBCT.

Assessment of treatment complications

CBCT scans are useful to assess complications such as fractured files and perforations. In cases where it is unlikely that a file can be removed, CBCT will provide information about the root canal morphology to determine if the file can be bypassed (Figures 4A-4G). Perforations on a buccal or palatal aspect may also be more clearly assessed with CBCT to determine the most appropriate management technique.

Assessment of root resorption

Assessment of root resorption

Conventional radiographic detection and assessment of root resorption may be challenging. This is compounded if the lesion is on the buccal or lingual/palatal aspect of the tooth where it will be masked by the more radiodense tooth structure. It may also be difficult to distinguish between internal inflammatory and external cervical root resorption from periapicals alone.

CBCT has been shown to be significantly more sensitive in detecting resorptive lesions (Estrela, et al., 2009) and also in assisting clinicians with choosing the correct treatment options (Patel, et al., 2009). The buccolingual extent of the resorption and assessment of perforations into the root canal or periodontal ligament can be more easily assessed with a CBCT. This will determine whether conventional treatment, surgery, or a combination of both is required.

This advance knowledge will enable treatment to be completed more efficiently and, in some cases, prevent patients undergoing unnecessary investigations on teeth (Figures 5A-5C). Preoperative CBCT scans should therefore be performed on all teeth with resorptive lesions that are potentially treatable.

Surgical planning

Surgical planning

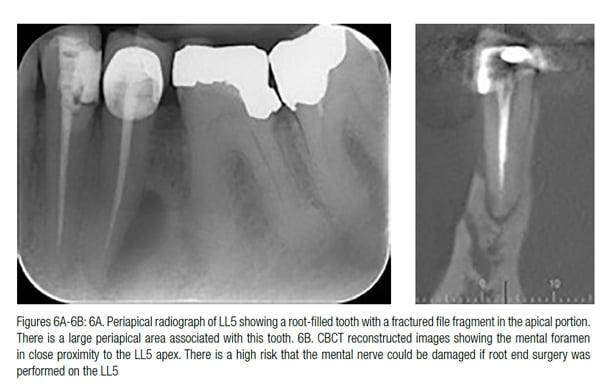

CBCT is useful in the planning of surgical endodontic procedures, as it will provide accurate information as to the size and location of the periapical lesion and root apex in relation to structures such as the maxillary sinus, inferior dental canal, and mental foramen (Figures 6A and 6B). Additional untreated canals (such as an MB2) may also be located. The amount of destruction of the cortical plates may also be assessed to determine whether membranes and grafting procedures are appropriate.

Conclusion

The use of CBCT in endodontics is rapidly increasing. Deciding when a CBCT is clinically necessary is a subject that causes great debate among endodontists. As ionizing radiation is used, it is essential that exposures are kept as low as reasonably achievable. Cases must therefore be assessed on an individual basis to determine whether the additional information from the scan will be beneficial in influencing the management of the case.

References

- Bender IB, Seltzer S. Roentgenographic and direct observation of experimental lesions in bone: I. J Am Dent Assoc. 1961;62:152-160.

- Bornstein MM, Wölner-Hanssen AB, Sendi P, von Arx T. Comparison of intraoral radiography and limited cone beam computed tomography for the assessment of root- fractured permanent teeth. Dent Traumatol. 2009;25:571-577.

- Brown J, Jacobs R, Levring Jäghagen E, et al. Basic training requirements for the use of dental CBCT by dentists: a position paper prepared by the European Academy of DentoMaxilloFacial Radiology. Dentomaxillofacl Radiol. 2014;43(1).

- Chang E, Lam E, Shah P, Azarpazhooh A. Cone-beam computed tomography for detecting vertical root fractures in endodontically treated teeth: a systematic review. J Endod. 2016;42(2):177-185.

- Davies A, Mannocci F, Mitchell P, Andiappan M, Patel S. The detection of periapical pathoses in root filled teeth using single and parallax periapical radiographs versus cone beam computed tomography — a clinical study. Int Endod J. 2015;48(6):582-592.

- Diangelis AJ, Andreasen JO, Ebeleseder KA, et al.; International Association of Association of Dental Traumatology. International Association of Dental Traumatology guidelines for the management of traumatic dental injuries: 1. Fractures and luxations of permanent teeth. Dent Traumatol. 2012;28(1):2-12.

- Durack C, Patel S. The use of cone beam computed tomography in the management of dens invaginatus affecting a strategic tooth in a patient affected by hypodontia: a case report. Int Endod J. 2011;44(5):474-83.

- Estrela C, Bueno MR, De Alencar AH, et al. Method to evaluate inflammatory root resorption by using cone beam computed tomography. J Endod. 2009;35(11):1491-1497.

- Gijbels F, Jacobs R, Sanderink G, et al. A comparison of the effective dose from scanography with periapical radiography. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2002;31(3):159-163.

- Huumonen S, Ørstavik D. Radiological aspects of apical periodontitis. Endod Topics. 2002;1(1):3-25.

- Loubele M, Bogaerts R, Van Dijck E, et al. Comparison between effective radiation dose of CBCT and MSCT scanners for dentomaxillofacial applications. Eur J Radiol. 2009;71(3):461-468.

- Orhan K, Aksoy U, Kalender A. Cone-beam computed tomographic evaluation of spontaneously healed root fracture. J Endod. 2010;36(9):1584-1587.

- Özen T, Kamburoğlu K, Cebeci AR, Yüksel SP, Paksoy CS. Interpretation of chemically created periapical lesions using 2 different dental cone-beam computerized tomography units, an intraoral digital sensor, and conventional film. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;107(3):426-432.

- Patel S, Dawood A, Whaites E, Pitt Ford T. New dimensions in endodontic imaging: part 1. Conventional and alternative radiographic systems. Int Endod J. 2009;42(6):447-462.

- Patel S, Dawood A, Wilson R, Horner K, Mannocci F. The detection and management of root resorption lesions using intraoral radiography and cone beam computed tomography – an in vivo investigation. Int Endod J. 2009;42(9):831-838.

- Patel S, Dawood A, Mannocci F, Wilson R, Pitt Ford T. Detection of periapical bone defects in human jaws using cone beam computed tomography and intraoral radiography. Int Endod J. 2009;42(6):507-515.

- Patel S, Brady E, Wilson R, Brown J, Mannocci F. The detection of vertical root fractures in root filled teeth with periapical radiographs and CBCT scans. Int Endod J. 2013;46(12):1140-1152.

- Patel S, Durack C, Abella F, Roig M, Shemesh H, Lambrechts P, Lemberg K. European Society of Endodontology position statement: the use of CBCT in endodontics. Int Endod J. 2014;47(6):502-504.

- Patel S, Durack C, Abella F, Shemesh H, Roig M, Lemburg K. Cone beam computed tomography in Endodontics — a review. Int Endod J. 2015;48:3-15.

- Patel S, Wilson R, Dawood F, Foschi F, Mannocci F. The detection of periapical pathosis using digital periapical radiography and cone beam computed tomography in endodontically retreated teeth — part 2: a 1-year post-treatment follow-up. Int Endod J. 2012;45(8):711-723.

- Stavropoulos A, Wenzel A. Accuracy of cone beam dental CT, intraoral digital and conventional film radiography for the detection of periapical lesions. An ex vivo study in pig jaws. Clin Oral Investig. 2007;11(1):101-106.